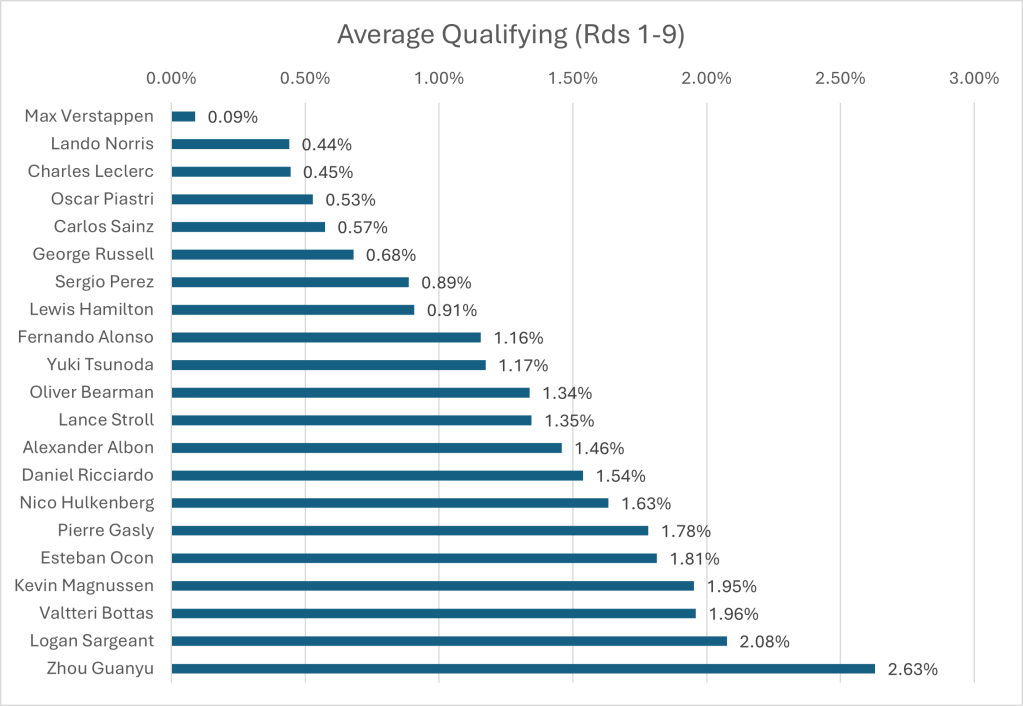

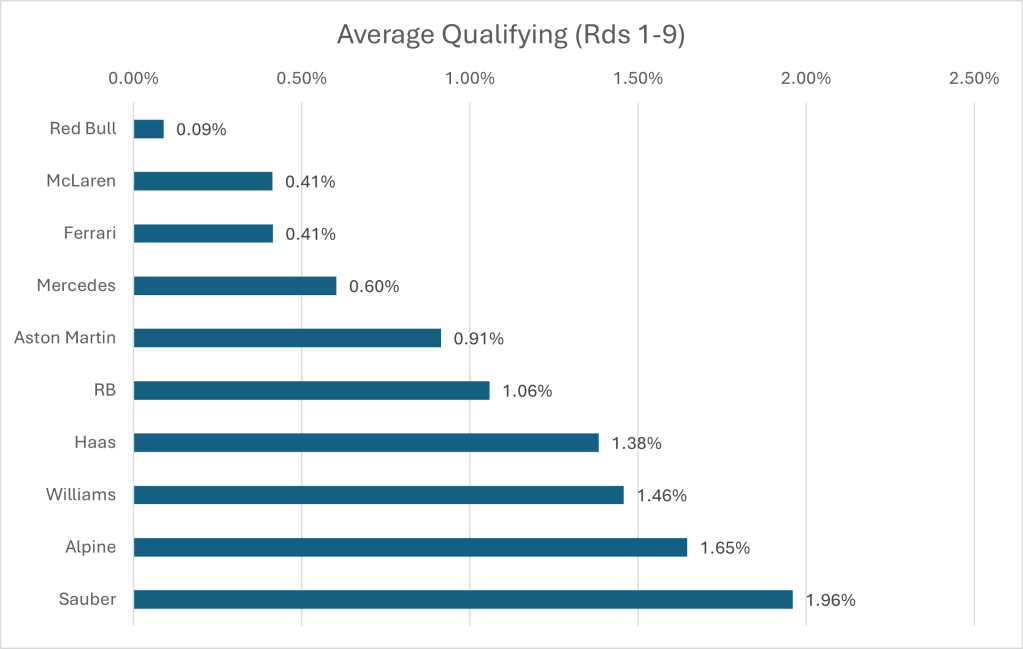

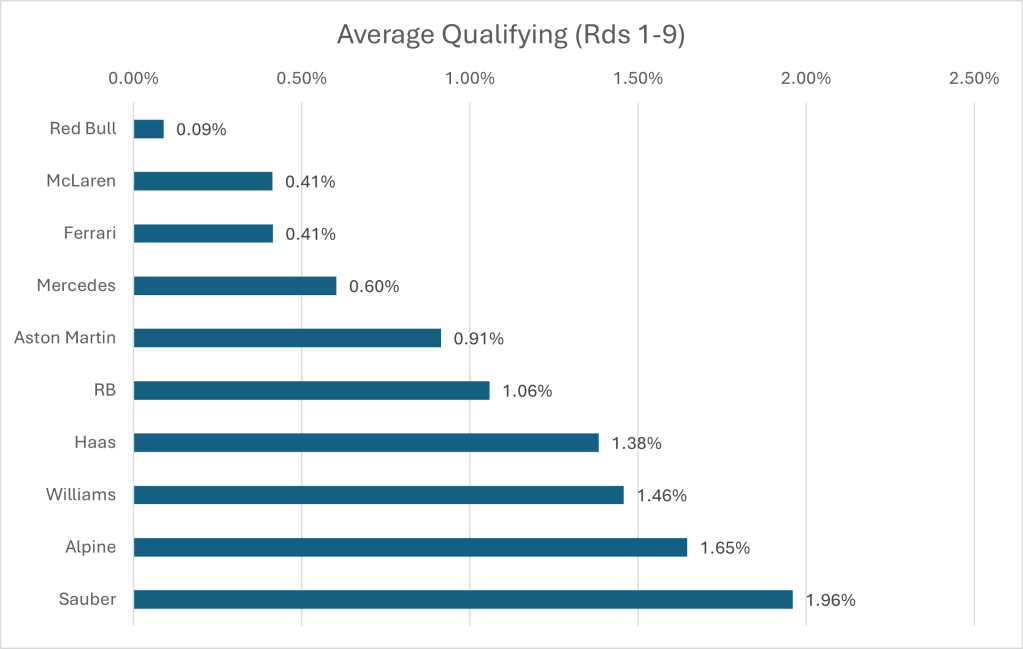

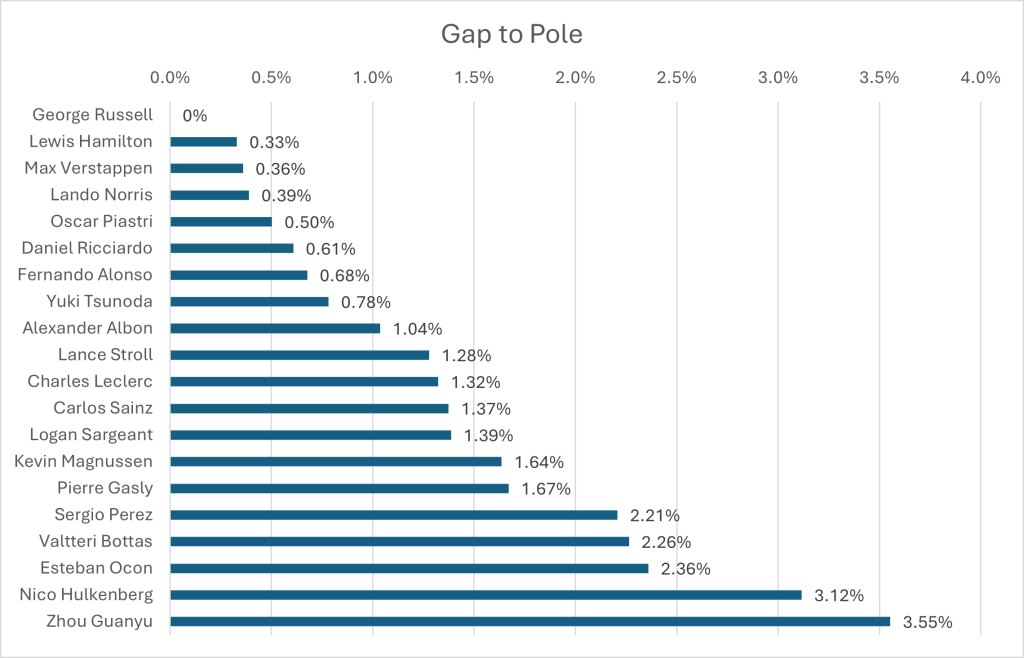

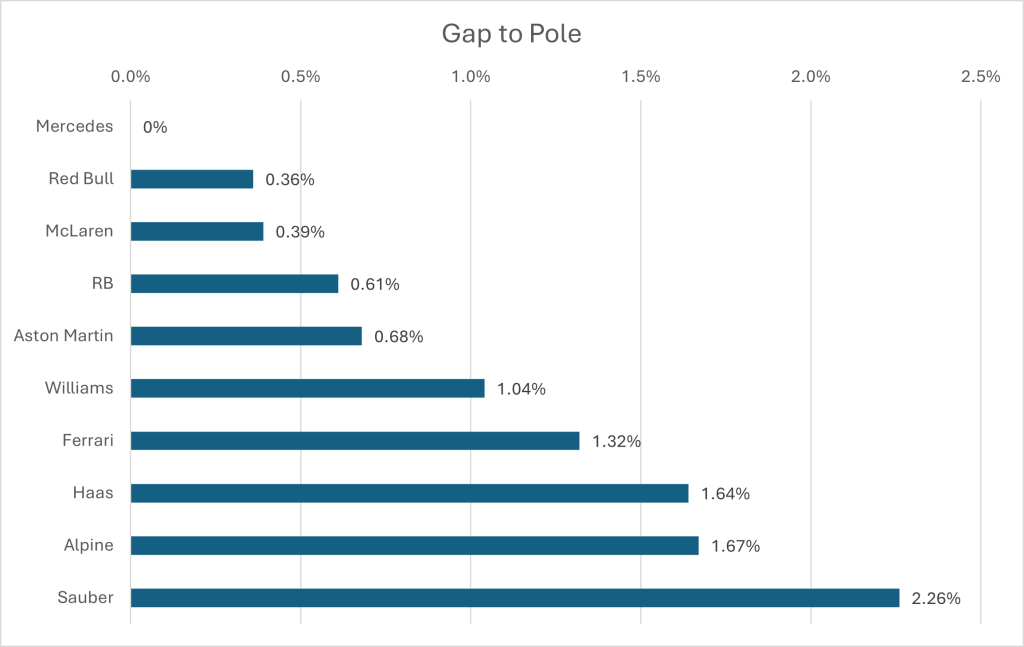

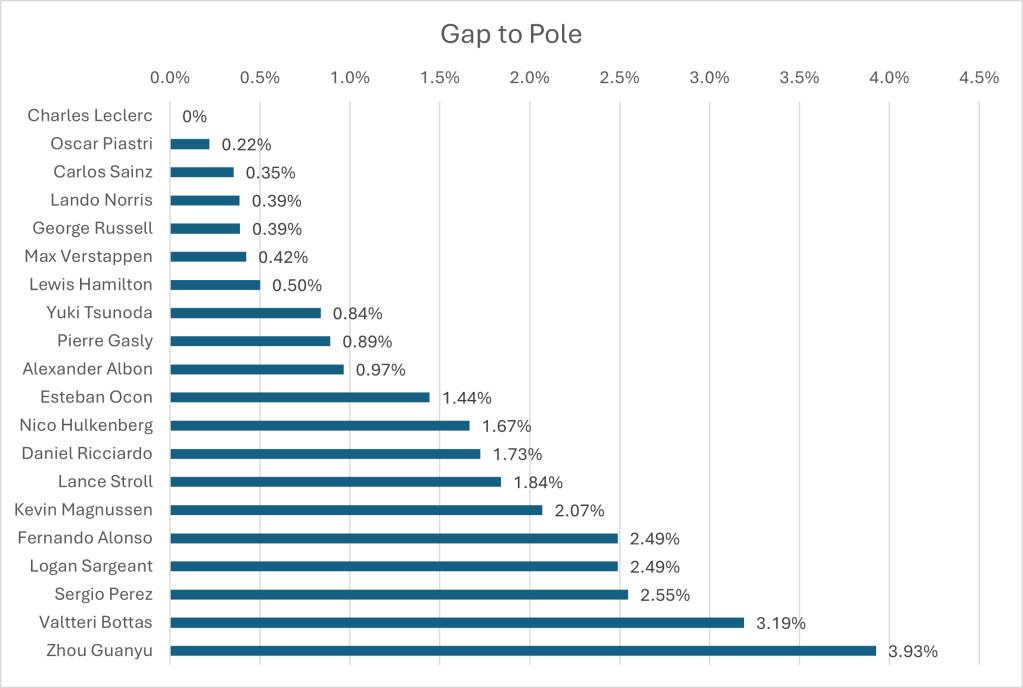

Qualifying Pace:

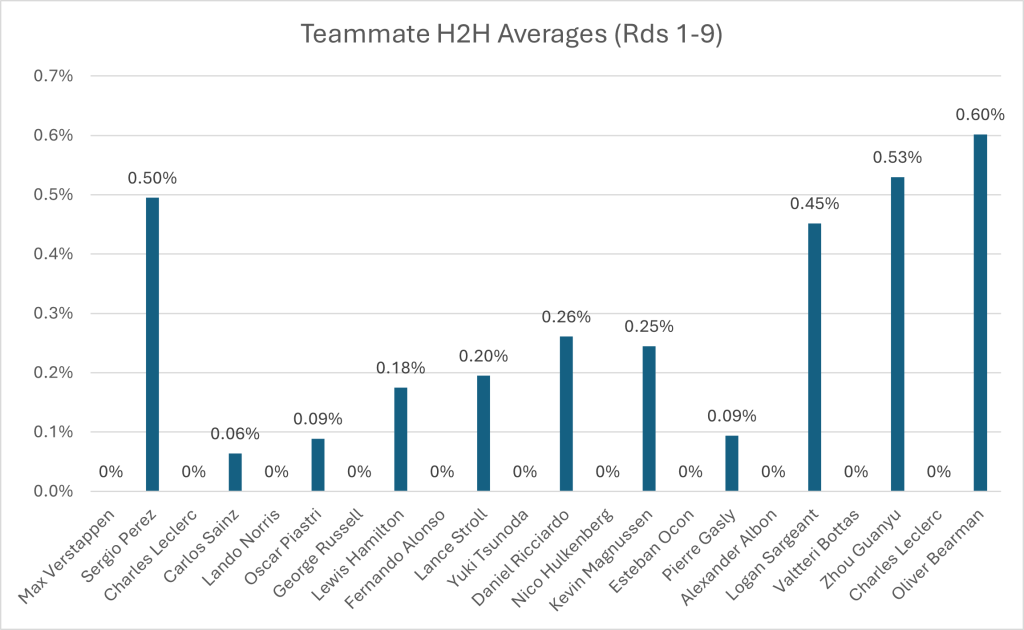

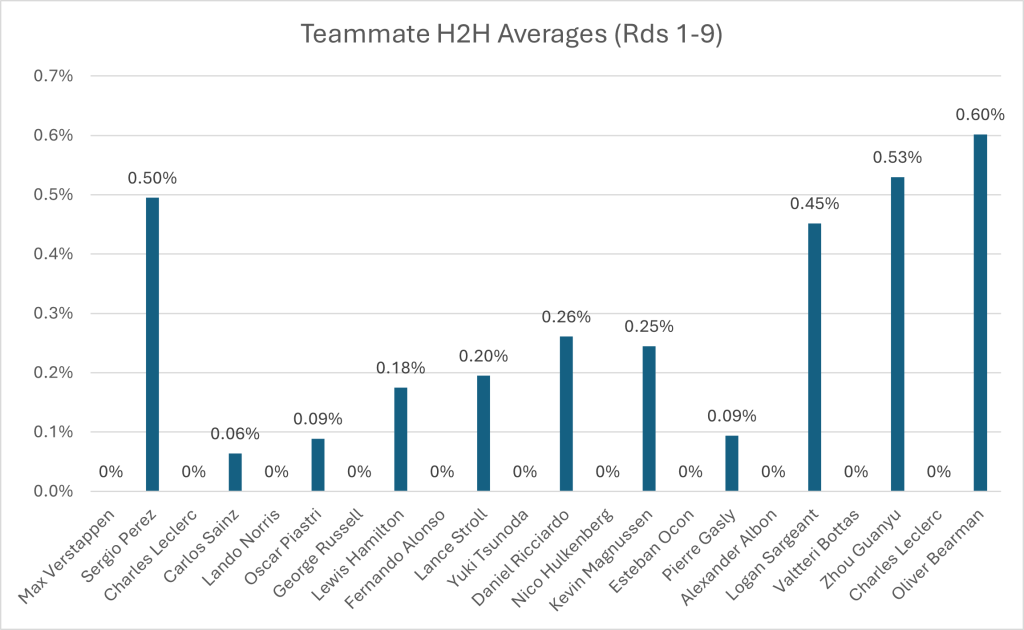

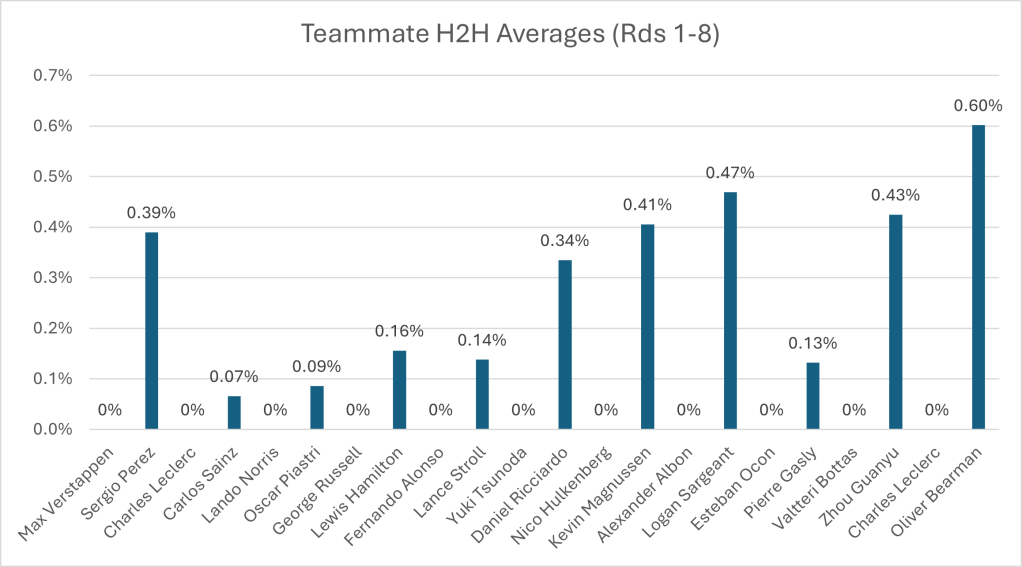

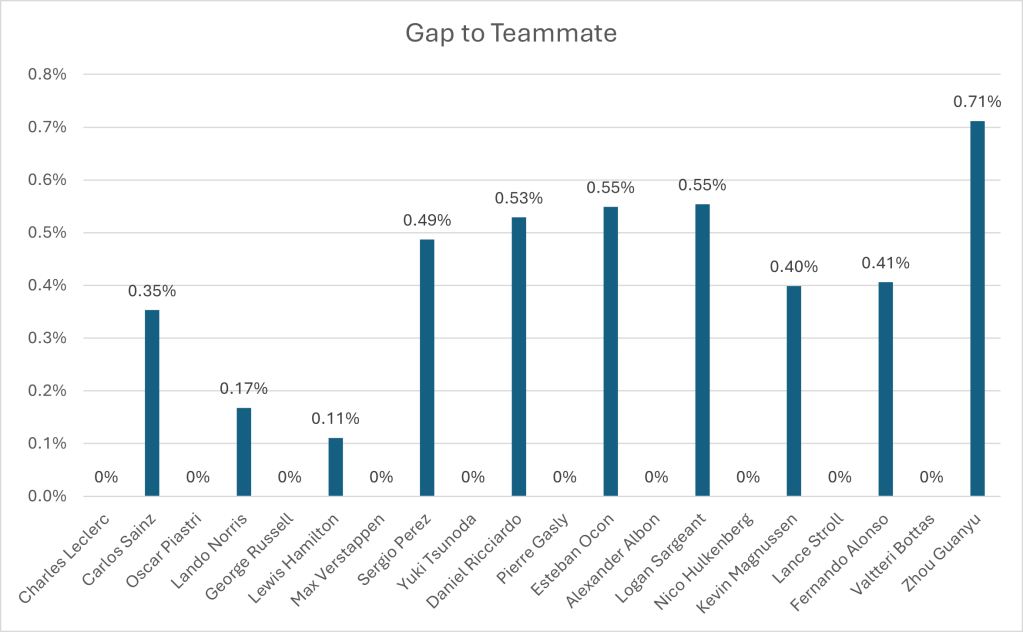

Teammate Head to Heads:

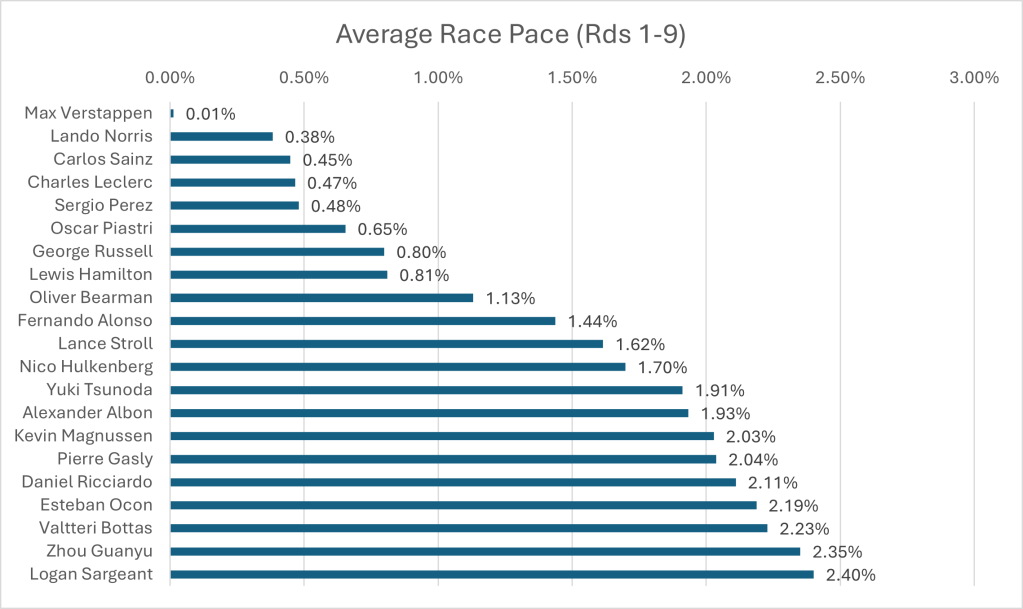

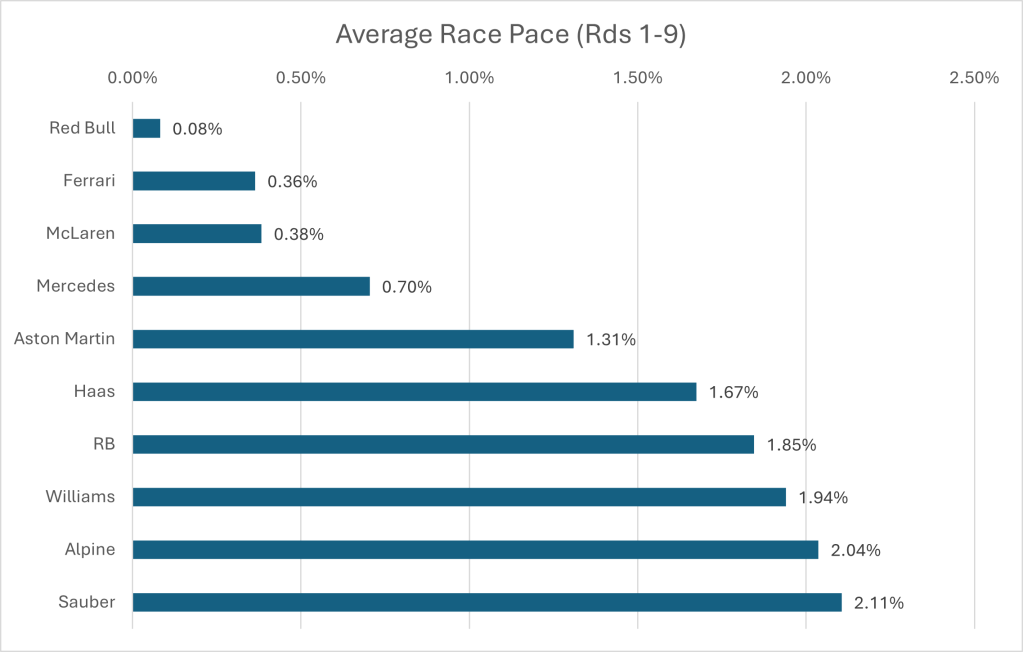

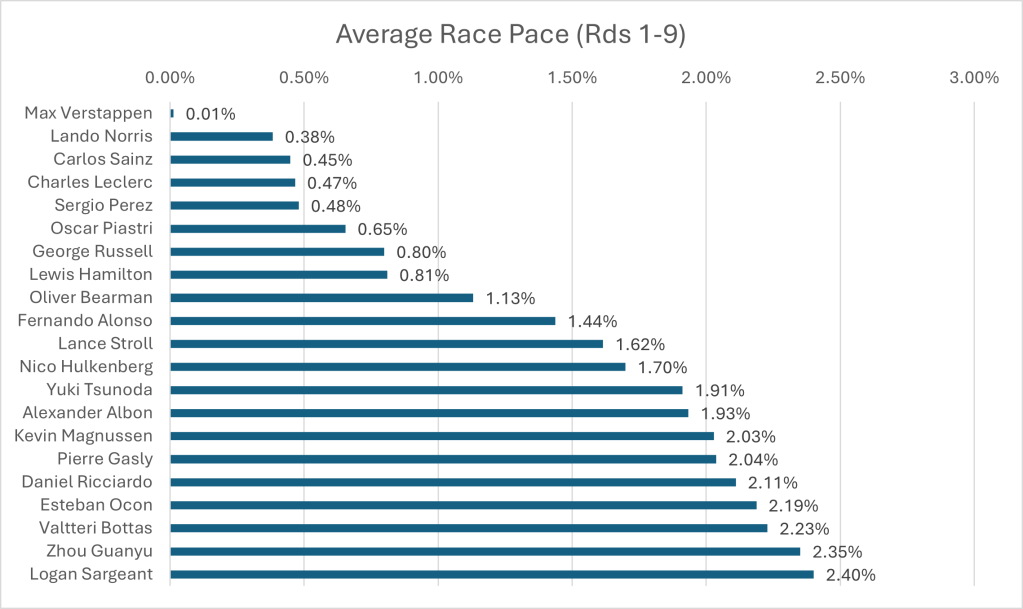

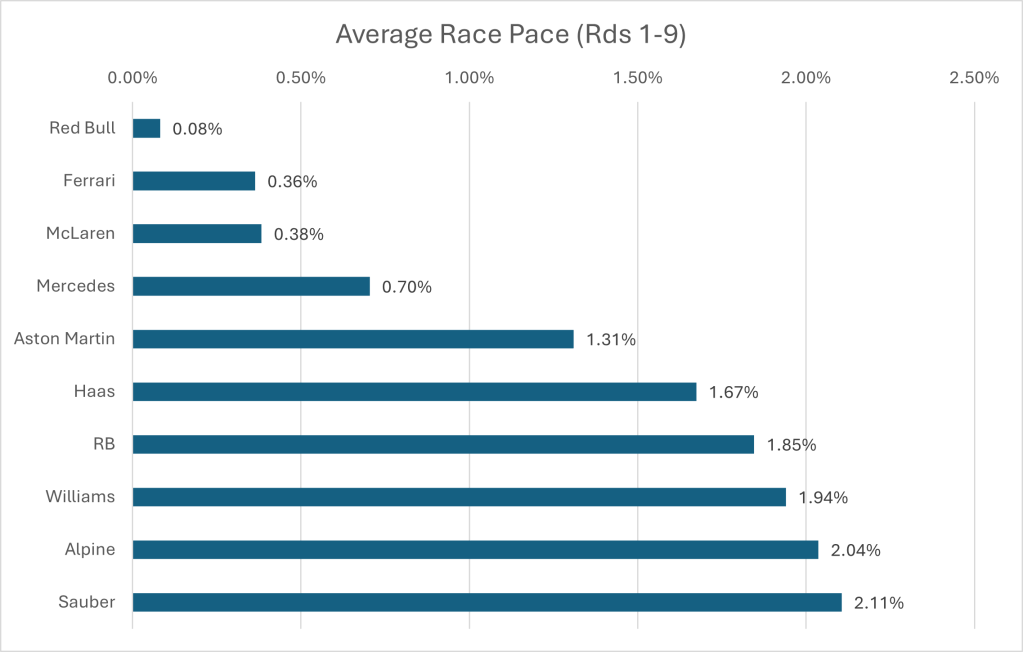

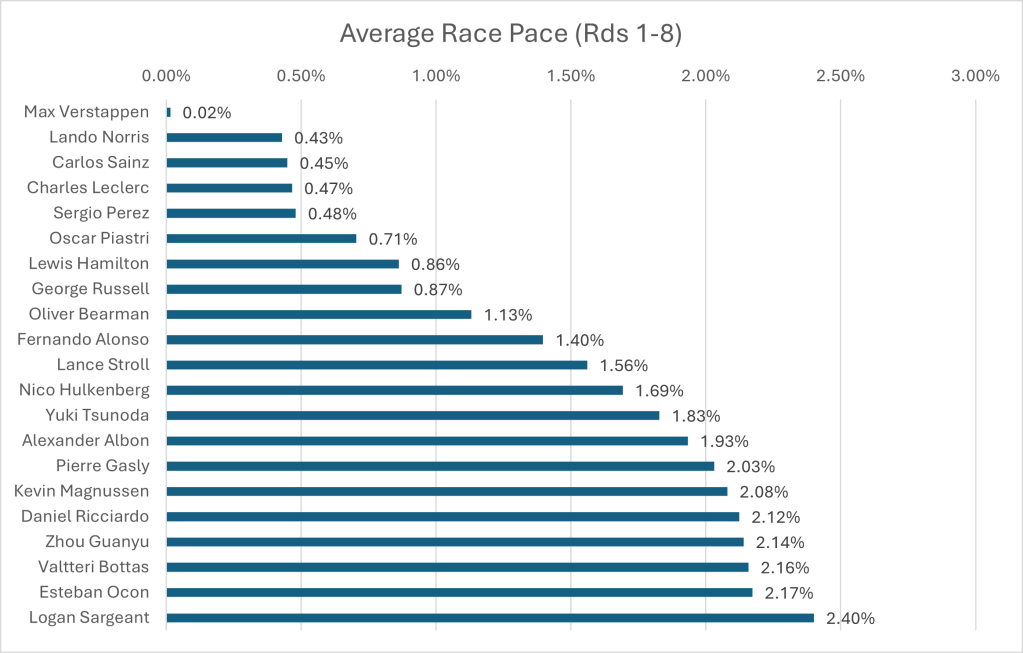

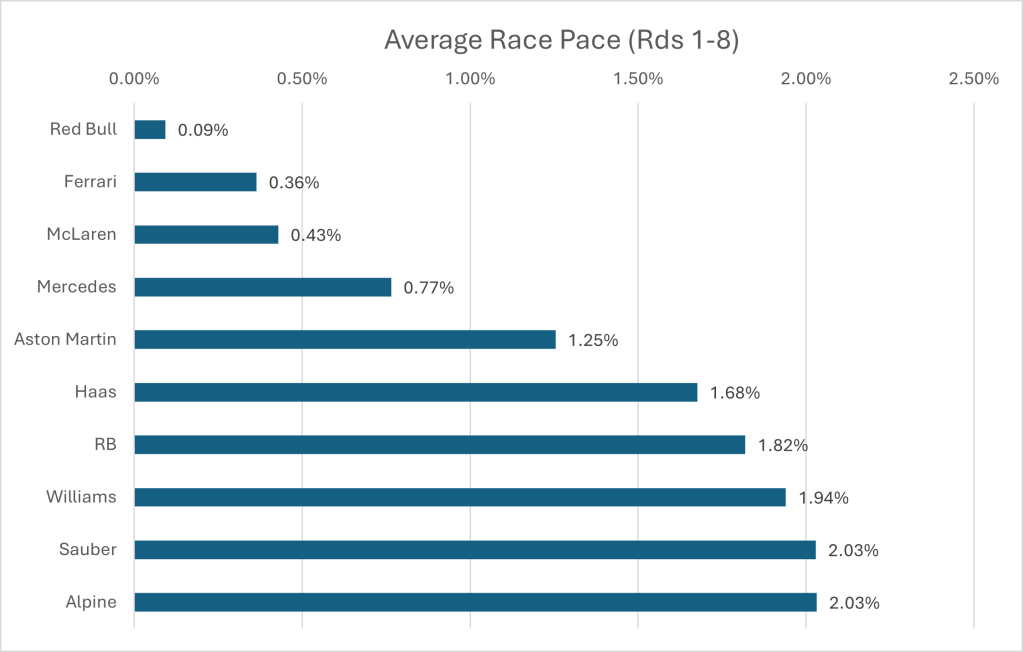

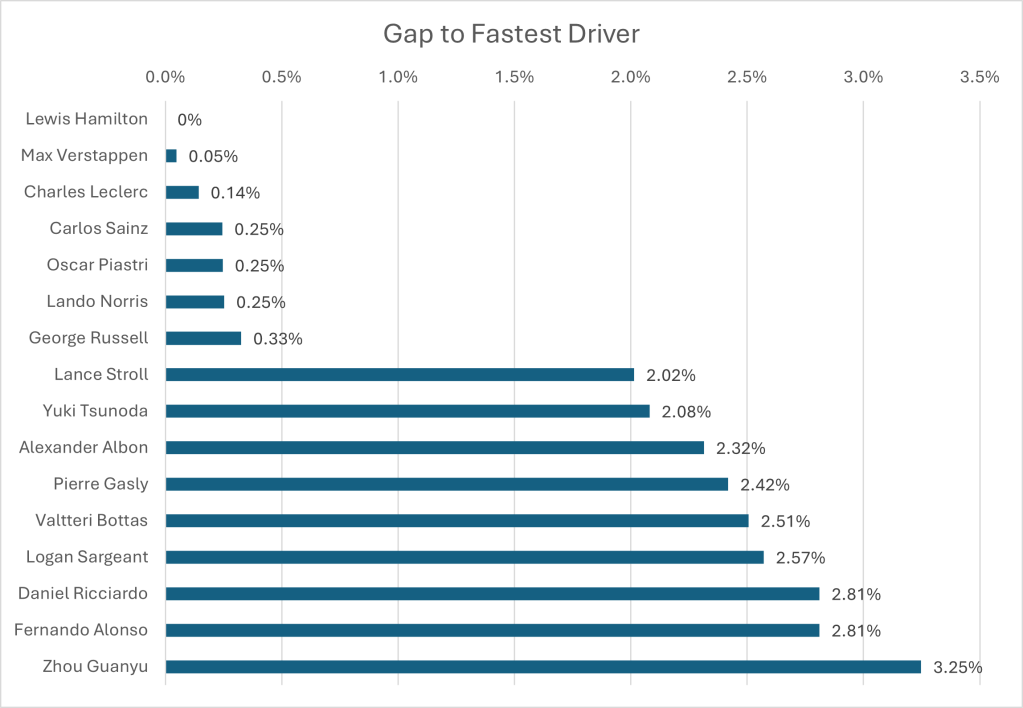

Average Race Pace:

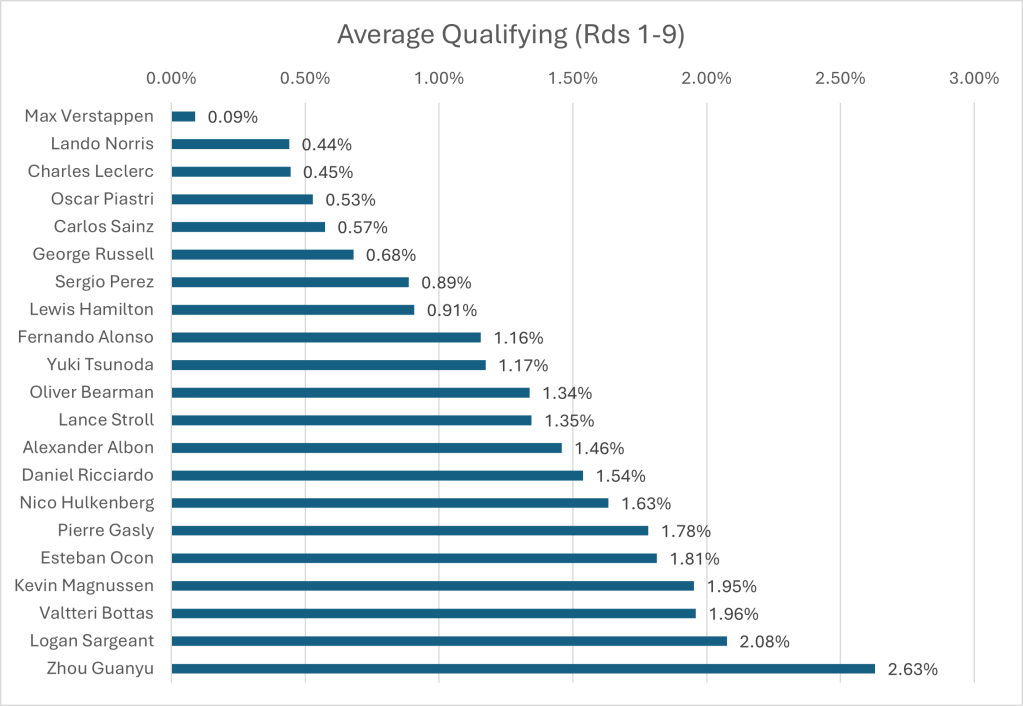

Qualifying Pace:

Teammate Head to Heads:

Average Race Pace:

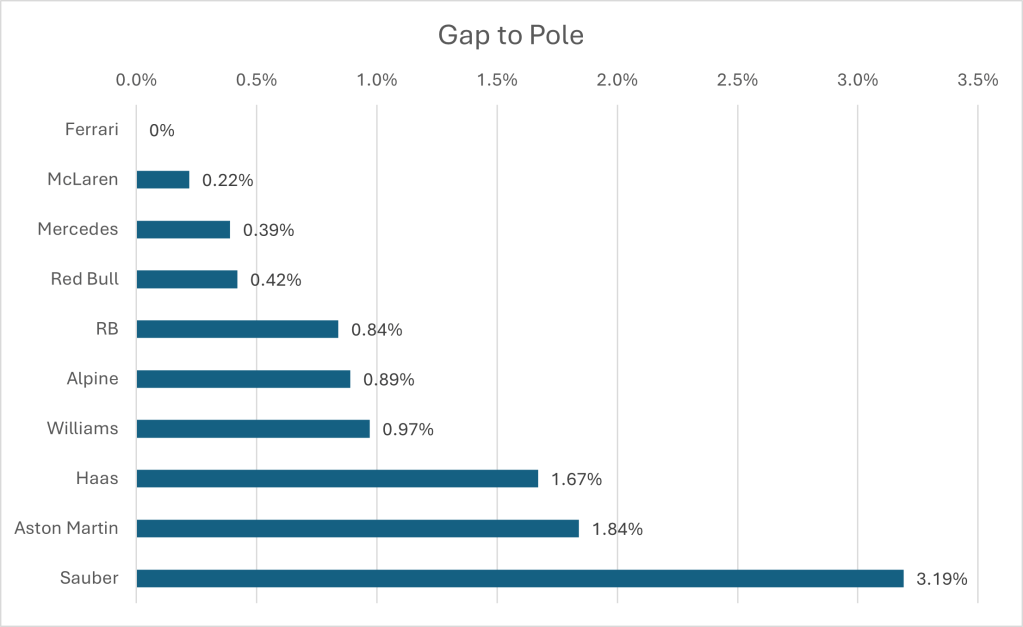

Qualifying Pace-

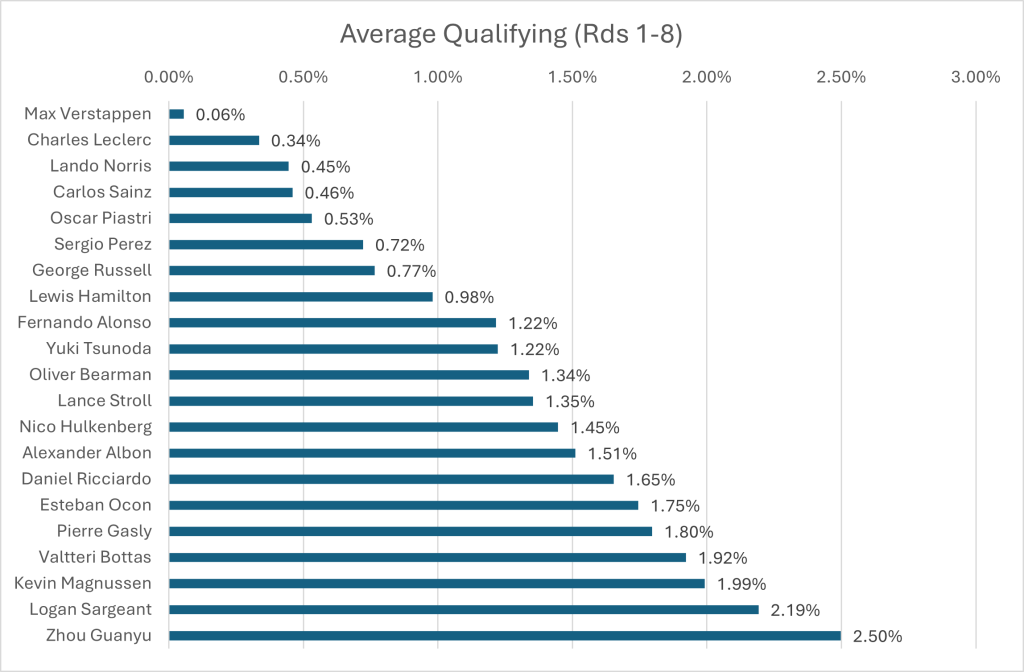

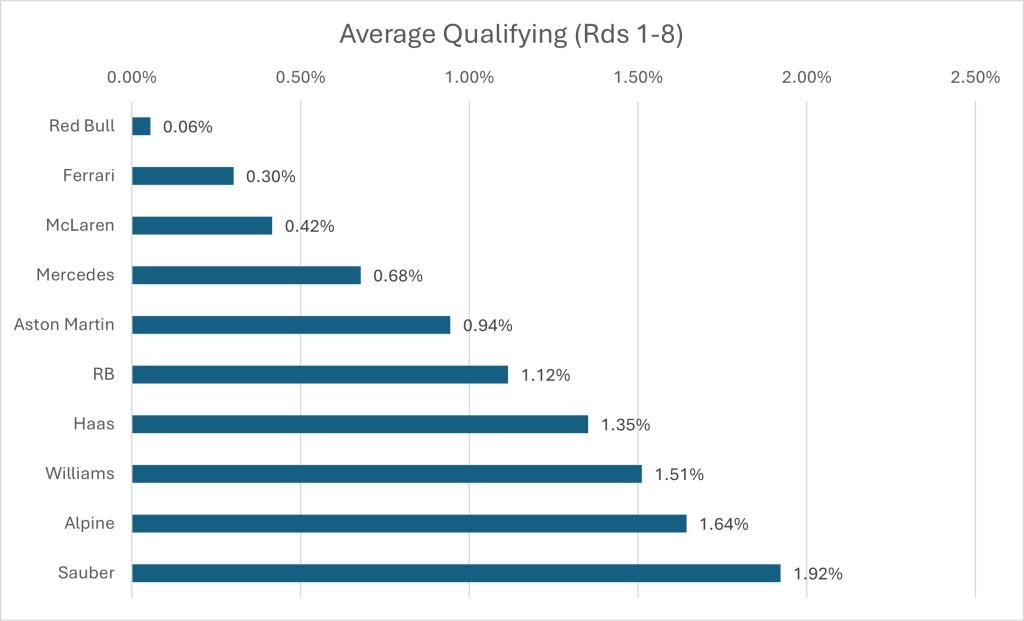

I have collated the fastest laps by each driver in qualifying, to show the average gap to the fastest driver. Whilst this extends the gap between drivers who made it to the top ten and those below, I’ve ruled using the overall fastest times a better grounding point for the true limit of the top cars, as the cars most likely to compete for points are my primary focus in these analyses.

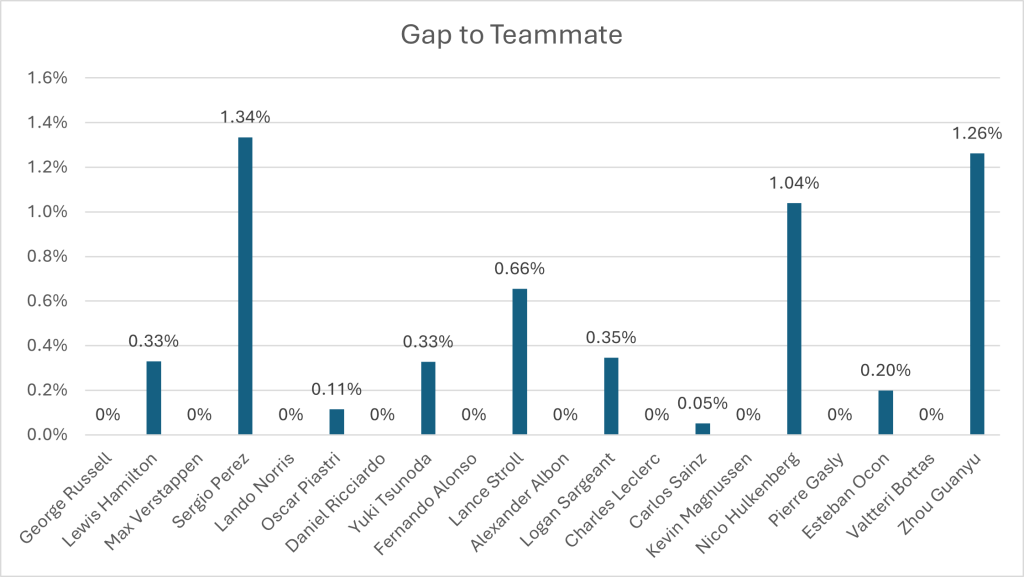

Additionally, I have collected the data for the gaps between teammates. I did this by using their lap times set in the same qualifying session. I generally compare the last session both drivers competed in, however if the fastest driver drove their fastest time in an earlier session, I count these times instead.

Race Pace-

I have calculated the average pace of the drivers, removing race starts, laps in the pit lane and laps under the safety car as these are all too slow to be representative. I have only included drivers that completed at least 75% of the laps to not skew the season averages against drivers that never got the chance to run their cars on low fuel, which excludes both Ferrari drivers, both Williams drivers and Sergio Perez in Canada

As different drivers have a varying number of race stints, this skews the overall pace. Generally, if a driver makes more stops, their pace will be faster on average. This will be considered in my final thoughts and analysis. Additionally, the average pace per stint and number of stints are recorded at the bottom of this article, for those interested in viewing more precise estimates of pace relative to other drivers on the same stint.[1]

Analysis:

Further Resources-

Qualifying Pace:

| Driver | Fastest Qualifying Time |

| George Russell | 71.742 (0%) |

| Lewis Hamilton | 71.979 (+0.330%) |

| Max Verstappen | 72 (+0.360%) |

| Lando Norris | 72.021 (+0.389%) |

| Oscar Piastri | 72.103 (+0.503%) |

| Daniel Ricciardo | 72.178 (+0.608%) |

| Fernando Alonso | 72.228 (+0.677%) |

| Yuki Tsunoda | 72.303 (+0.782%) |

| Alexander Albon | 72.485 (+1.036%) |

| Lance Stroll | 72.659 (+1.278%) |

| Charles Leclerc | 72.691 (+1.323%) |

| Carlos Sainz | 72.728 (+1.374%) |

| Logan Sargeant | 72.736 (+1.386%) |

| Kevin Magnussen | 72.916 (+1.636%) |

| Pierre Gasly | 72.94 (+1.670%) |

| Sergio Perez | 73.326 (+2.208%) |

| Valtteri Bottas | 73.366 (+2.264%) |

| Esteban Ocon | 73.435 (+2.360%) |

| Nico Hulkenberg | 73.978 (+3.117%) |

| Zhou Guanyu | 74.292 (+3.554%) |

Average Race Pace:

| Driver | Pace |

| Max Verstappen | 84.824 (0%) |

| Lando Norris | 84.834 (+0.012%) |

| George Russell | 85.011 (+0.220%) |

| Oscar Piastri | 85.037 (+0.251%) |

| Lewis Hamilton | 85.197 (+0.440%) |

| Kevin Magnussen | 86.233 (+1.662%) |

| Nico Hulkenberg | 86.299 (+1.739%) |

| Fernando Alonso | 86.318 (+1.761%) |

| Lance Stroll | 86.518 (+1.998%) |

| Daniel Ricciardo | 86.546 (+2.030%) |

| Pierre Gasly | 86.583 (+2.074%) |

| Esteban Ocon | 86.763 (+2.286%) |

| Yuki Tsunoda | 86.947 (+2.503%) |

| Valtteri Bottas | 87.131 (+2.720%) |

| Zhou Guanyu | 88.073 (+3.830%) |

All Stints:

| Best Stints | Pace |

| Hamilton 4th (11L/NH) | 76.154 |

| Russell 4th (11L/NM) | 76.187 |

| Norris 3rd (16L/NM) | 77.001 |

| Verstappen 3rd (18L/NM) | 77.31 |

| Magnussen 5th (11L/NM) | 77.82 |

| Piastri 3rd (19L/NM) | 78.191 |

| Alonso 3rd (18L/NH) | 79.083 |

| Hulkenberg 4th (18L/NM) | 79.167 |

| Stroll 3rd (18L/UH) | 79.224 |

| Ricciardo 3rd (19L/UM) | 79.572 |

| Ocon 2nd (18L/NM) | 79.475 |

| Zhou 4th (13L/NM) | 79.475 |

| Russell 3rd (7L/NH) | 79.774 |

| Tsunoda 2nd (17L/NM) | 79.95 |

| Gasly 3rd (22L/NH) | 80.078 |

| Bottas 2nd (20L/NM) | 80.575 |

| Hamilton 3rd (9L/NM) | 80.743 |

| Sainz 3rd (8L/NM) | 81.445 |

| Albon 3rd (7L/NM) | 81.555 |

| Perez 3rd (7L/NM) | 81.764 |

| Magnussen 4th (10L/NM) | 83.141 |

| Norris 2nd (17L/NI) | 86.099 |

| Verstappen 2nd (15L/NI) | 86.272 |

| Russell 2nd (15L/NI) | 86.468 |

| Piastri 2nd (14L/NI) | 86.692 |

| Hamilton 2nd (13L/NI) | 86.868 |

| Alonso 2nd (14L/NI) | 87.596 |

| Zhou 3rd (6L/NM) | 87.616 |

| Hulkenberg 2nd (10L/NI) | 87.783 |

| Hulkenberg 3rd (13L/NI) | 87.833 |

| Stroll 2nd (14L/NI) | 87.868 |

| Albon 2nd (14L/NI) | 87.964 |

| Leclerc 4th (8L/NI) | 88.168 |

| Perez 2nd (13L/NI) | 88.329 |

| Ricciardo 2nd (13L/NI) | 88.334 |

| Sainz 2nd (13L/NI) | 88.42 |

| Zhou 2nd (14L/NI) | 88.935 |

| Magnussen 3rd (11L/NI) | 89.092 |

| Gasly 2nd (10L/NI) | 89.15 |

| Magnussen 2nd (16L/NI) | 89.179 |

| Norris 1st (23L/NI) | 89.349 |

| Piastri 1st (23L/NI) | 89.685 |

| Verstappen 1st (23L/NI) | 89.759 |

| Russell 1st (23L/NI) | 89.873 |

| Tsunoda 1st (37/NI) | 90.161 |

| Ocon 1st (37L/NI) | 90.308 |

| Hamilton 1st (23L/NI) | 90.321 |

| Bottas 1st (35L/NI) | 90.878 |

| Alonso 1st (23L/NI) | 91.201 |

| Ricciardo 1st (23L/NI) | 91.297 |

| Stroll 1st (23L/NI) | 91.405 |

| Albon 1st (23L/NI) | 91.531 |

| Sainz 1st (23L/NI) | 91.621 |

| Gasly 1st (23L/NI) | 91.69 |

| Leclerc 1st (23L/NI) | 91.754 |

| Sargeant 1st (21L/NI) | 91.834 |

| Perez 1st (23L/NI) | 91.898 |

| Zhou 1st (23L/NI) | 92.729 |

| Magnussen 1st (5L/NW) | 95.212 |

| Hulkenberg 1st (10L/NW) | 95.656 |

[1] I only include stints in the stint table if a driver has completed five or more representative laps, in an attempt to avoid fastest lap attempts. This has led to exclusions from the chart of Leclerc’s second and third stints.

After a disastrous Detroit it was a relief to see IndyCar put on a decent race. Whilst overshadowed on the day by the brilliant Canadian Grand Prix, Road America was still a fun to watch and was bolstered by a two-year win drought coming to an end.

After qualifying, it appeared that a good race was in store for the Chip Ganassi drivers not called Dixon or Palou. Rookie Linus Lundqvist took his maiden pole, with Marcus Armstong slotting behind in third. Another driver feeling confident was Colton Herta, who needed to bounce back from a couple of self-inflicted errors. With Herta in second, the Chip Ganassi and Andretti teams held unbridled optimism. Unfortunately, with less experience comes less experience, which Linus Lundqvist promptly discovered when his teammate slammed into the back of him, ruining their races. Yet Colton Herta also wasn’t immune from the rear ending, as he was hit by the far more experienced Josef Newgarden. Armstrong received a deserved penalty, yet Newgarden was not, which appeared quite bizarre as both incidents were almost identical. Some would say that a member of the team already found to have cheated this year not being penalized was suspicious. Some would also say that when the owner of that team also owns IndyCar, that makes the situation even more suspicious. I would not say that, for I am incredibly neutral. Still… some would say.

With most of the opposition out of the way, it became easier for Team Penske to show their pace. Penske had opted for a low drag set up, making it incredibly easy for them to make overtakes on the straights. Scott McLaughlin proved this after the first caution, when he swept past Kyle Kirkwood to take the lead. An additional caution brought out by Kyffin Simpson’s crash made Penske’s job even easier. McLaughlin thus found himself leading a Penske 1-2-3. Yet, in what is becoming a common theme this season, drivers risked losing their position if they failed to manage the softer red tyres. These tyres degraded quickly, as was proven when Scott Dixon fell down the field to finish in twenty-first, having earlier ran as high as fifth. Josef Newgarden had already completed his red stint at the beginning of the race, so it would be up to Scott McLaughlin and Will Power to manage their red stints, or risk losing everything.

McLaughlin and Power managed their red stints perfectly, so McLaughlin still led a Penske 1-2-3 before the last round of pit stops. As McLaughlin was in front, the team elected to pit him a lap before Josef Newgarden in second. However, Newgarden overcut McLaughlin and had a healthy lead after his stop. However, as Will Power was third to come in, this did not last for Newgarden and the top three ended up in the reverse order of where they’d started. Will Power proceeded to drive a perfect final stint to take his first win in two years, along with the lead of the championship. Whilst Power largely had this win fall into his arms, it made me happy to see his drought end. Will Power seems like a very kind and quirky man, who deserves to still be fighting at the front in IndyCar.

Overall, the race was very normal. But normal for IndyCar is still a fun watch. All three Team Penske drivers have now won races and have had great pace this year. As IndyCar is soon to move into its oval races, where Penske have historically been stronger, Scott Dixon and Alex Palou are going to have a fight on their hands to win this championship.

Along with Imola, this race has to go down as one of Verstappen’s greatest victories. In the trickiest of conditions, no driver was perfect, but Verstappen made the least mistakes, in a car that seldom appeared the fastest.

2. George Russell-

George may have made a few mistakes throughout the race, but it was still a fabulous performance. In a track that his teammate has often excelled at, George once again proved that he is currently the fastest and most reliable Mercedes driver, to duly deliver his team their first podium of the year.

3. Alexander Albon-

Whilst a late spin from Sainz took Albon out of the race, he reminded everyone the fighter he is with his performance throughout the race. In particular, his double overtake on Ricciardo and Ocon, where he slipped through the tiniest gap in the middle of the two cars, was sublime.

4. Daniel Ricciardo-

After justified criticism from Jacques Villeneuve, Daniel decided to show up this week, qualifying in fifth and finishing the race in eighth, despite a jump start penalty. It was a solid performance and if Daniel can keep these up, he will justify why he should stay in Formula One.

5. Alpine-

I’m breaking my rules again and giving half a point to each of the Alpine drivers. Esteban Ocon drove from the back of the grid into the points, which is always worth a shout out and Pierre Gasly also delivered a points finish. Despite a post-race controversy about a controversial driver swap at the end of the race, both drivers showed their talents still shine through in a bad car.

Tally:

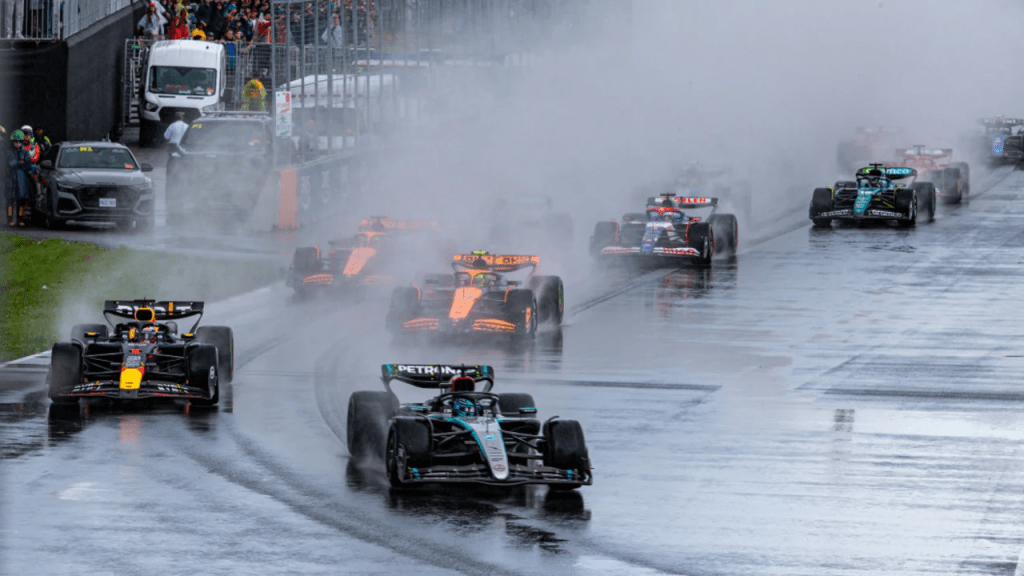

Thrilling conditions often bespoke a thrilling race. Which is exactly what Formula One provided in Canada. Featuring a three-way battle for the win, incidents aplenty and Alex Albon making the overtake of the year, Canada delivered a wet-to-dry classic that fans will be talking about for years to come.

After an equally thrilling qualifying, which saw George Russell and Max Verstappen set the exact same pole time, conditions at the start of the race were incredibly wet. As all the runners on the intermediate tyres struggled for grip, one team made moves across the field. As Haas had elected to start on the wet tyres, they were instantly the fastest cars on the circuit. My favourite chaos merchant Kevin Magnussen made fine use of his extra grip, moving from fourteenth to fourth in the space of a few laps. It seemed like Haas had made a fantastic gamble, but within a few laps, as the track started to dry, conditions moved towards the intermediate runners. It was at this point that Haas needed to bring Kevin in for a pit stop. They did this, albeit forgetting to bring the tyres. So, Kevin’s work was all for nought, as he fell down the field, throwing away a chance of points. It was a shame to see Kevin’s performance yield no rewards, as he reminded everyone that when he’s not courting controversy, he’s a damn good racer.

As all the midfield chaos was occurring, George Russell was leading with Verstappen hot on his tail. The Mercedes showed a surprising flash of pace this weekend, likely bolstered by their upgrades and the colder conditions in Canada. After not being close to the podium all season, Russell was a legitimate contender for the win. It was a great turnaround, though as the two frontrunners fought, the McLaren’s of Norris and Piastri were getting closer and closer. McLaren had set their car up to prioritise tyre wear and this began to pay off, as Norris overtook both Verstappen and Russell to lead the race. He then began to pull away from the field and it began to appear like Lando’s second win was on the horizon. Then Logan Sargeant crashed and bought out the safety car. From here, things began to fall apart for Lando.

When the safety car was called, McLaren had just enough time to bring in Lando for a pit stop.[1] Unfortunately for them, they missed their opportunity, continuing an under-scrutinized trend of McLaren making poor strategic decisions at vital moments. As all the other front runners pitted, Norris had to complete another lap behind the safety car, resulting in him falling from first to third when he finally did pit. Norris would never regain the opportunity to win the race from this point onwards, despite attempting an overcut when switching to dry tyres. Whilst finishing second, this result was not was Norris was hoping for. Combined with the near miss at Imola, Norris has missed out on possible victories in two of the last three races. For a team that finally seems to have a championship contending car, McLaren have to take these opportunities.

As the race reached its dry zenith, it was the Mercedes of George Russell that looked to have the pace to challenge for Verstappen for the win. Yet, a series of small, costly errors throughout the race consistently put Russell into fights with other frontrunners that he could have avoided. This is a consistent trend many have noticed about George Russell. He is a fantastic driver, with supreme qualifying abilities and great race pace, but he makes mistakes at the exact wrong moments. At minimum, he could have finished second with his pace towards the end of the race, but instead had to settle for third. It was still a fantastic performance throughout the weekend for George, but he’s got to have to turn this narrative around soon. If Mercedes’ upgrade path is as fruitful as some are predicting, perhaps that opportunity could arise in Spain. If it does, George has to take it.

With such a fantastic race, the only thing that could possibly make me upset would be if Ferrari were to have an absolute howler. If, for example, they were to both qualify outside the top-10, then have race-ending engine issues on my favourite driver’s car, I would be upset. I would be even more upset if Ferrari’s other driver then proceeded to spin out of the race, in the process hitting my second favourite driver, who up to that point was having a brilliant race. For the sake of praising one of the best Formula One races of the last few years, I am going to choose to no longer ruminate on the fact that these exact events occurred.

So, despite certain events, this race had everything. Three teams fighting for the win, battles across the field, strategy gambles and Max Verstappen delivering a masterclass performance to remind everyone that even without a dominant car, he is a dominant driver. I won’t be forgetting this one anytime soon.

[1] Mark Hughes, MONDAY MORNING DEBRIEF: Norris would likely have won in Canada had he pitted under the Safety Car – so why didn’t he?, (10 June 2024) https://www.formula1.com/en/latest/article/monday-morning-debrief-norris-would-likely-have-won-in-canada-had-he-pitted.1Dyef4xy7eJDmKpNAYgdKY

Whoever’s idea it was to follow up the excitement of the Indy500 with a race at a terrible street track in downtown Detroit needs to reflect on what they’ve done. Anyone who had watched the 500 and wanted to see what else IndyCar has to offer may not watch another race. With a track that is essentially a worse version of Baku, itself one of F1’s worst tracks, I expected the race to either be boring or chaotic to the point of frustration. Having now seen the second option play out, I really wish that this race was boring.

It’s unfortunate how the race unfolded, because the opening stint left some hope that it had some potential. This was because the teams mistakenly presumed that the softer green tyres would be preferrable. When Alex Palou, who had started the race in second on the greens, had to pit after dropping through the field like a boulder, it became apparent the harder black tyres were better. Realizing this, many teams prepared to adapt their strategies for a race that could have developed into an interesting tyre war. Instead, it began to rain.

Under a caution period, the track began to resemble a duck pond. At this point, many drivers, including the leading Colton Herta, pit for wet weather tyres. Then it stopped raining, whilst the safety car was still out. As the track dried up, every driver who had pitted regretted their choice, realizing they had handed a valuable win to Scott Dixon. Dixon managing to pull off one of his famous fuel saving strategies to take the win was the only saving grace from here on out. And even then, a Dixon master class is less impressive when nearly half the race was run under caution periods, due to events spiralling into some sort of demolition derby.

The aforementioned derby was not entertaining. Nearly every driver forgot what a braking point was and slammed into the sides of their competitors. Colton Herta was the only exception to this, preferring to miss his braking point so much that he slammed directly into the tyres at the end of the escape road. After having dominated the early stages of the race, Colton made another unforced error when he found himself lower down the field. His move was both emblematic of his championship challenge collapsing and a general lack of adherence to expected driving standards. It was not a great showing for the sensibilities of IndyCar’s drivers and destroyed whatever entertainment could have been salvaged out of the weekend.

Whilst personally dissatisfied at some of the racing standards on display, one thing from the Detroit weekend’s aftermath stuck out. You do not, under any circumstances, send abuse and death threats to anyone, for any reason, ever. This has been the warrant of a subsection of Augustin Canapino fans, who act like football ultras to anyone who crosses Augustin’s path. Theo Pourchaire was the target of abuse this time around, all for contact that was relatively minor compared to some of the incidents that took place during the race.[1] The abuse itself is already problematic, but Canapino’s response beggared belief, as he focused on how his fans were not responsible and questioned if Theo received death threats due to not having personally seen them.[2] This led to Augustin not racing at Road America and his team’s partnership with McLaren being terminated. Yet, Augustin’s response was not even the worst element of the whole debacle. That came from the team owner, Ricardo Juncos, who was heard calling Theo a ‘son of 1,000 wh***s.[3]’ It would be one thing for a driver, in the heat of the moment, to use inappropriate language towards a competitor. When the team owner is doing it, that speaks to a broader workplace cultural problem. And not only did Ricardo Juncos use inappropriate language, he used deeply misogynistic language, language that would not even come into my head to describe my worst enemy. All this, for minor contact. Juncos Hollinger need to do better.

[1] https://x.com/TPourchaire/status/1797751884700127467

[2] https://x.com/AgustinCanapino/status/1797956262573043725

[3] https://www.planetf1.com/news/theo-pourchaire-hate-death-threats-indycar

Pole Position: Lando Norris

Bold Prediction: Both Aston’s make Q3

Average Qualifying:

Teammate Head to Heads:

Average Race Pace:

I have collated the fastest laps by each driver in qualifying, to show the average gap to the fastest driver. Whilst this extends the gap between drivers who made it to the top ten and those below, I’ve ruled using the overall fastest times a better grounding point for the true limit of the top cars, as the cars most likely to compete for points are my primary focus in these analyses.

Qualifying Pace-

Additionally, I have collected the data for the gaps between teammates. I did this by using their lap times set in the same qualifying session. I generally compare the last session both drivers competed in, however if the fastest driver drove their fastest time in an earlier session, I count these times instead.

Race Pace-

I have calculated the average pace of the drivers, removing race starts, laps in the pit lane and extra formation laps as these are all too slow to be representative. I have only included drivers that completed at least 75% of the laps to not skew the season averages against drivers that never got the chance to run their cars on low fuel, which excludes Esteban Ocon, Sergio Perez and both Haas drivers in Monaco.

As different drivers have a varying number of race stints, this skews the overall pace. Generally, if a driver makes more stops, their pace will be faster on average. This will be considered in my final thoughts and analysis. Additionally, the average pace per stint and number of stints are recorded at the bottom of this article, for those interested in viewing more precise estimates of pace relative to other drivers on the same stint.[1]

Analysis:

Further Resources-

Qualifying Pace:

| Driver | Fastest Qualifying Time |

| Charles Leclerc | 70.27 (0%) |

| Oscar Piastri | 70.424 (+0.219%) |

| Carlos Sainz | 70.518 (+0.353%) |

| Lando Norris | 70.542 (+0.387%) |

| George Russell | 70.543 (+0.389%) |

| Max Verstappen | 70.567 (+0.423%) |

| Lewis Hamilton | 70.621 (+0.500%) |

| Yuki Tsunoda | 70.858 (+0.837%) |

| Pierre Gasly | 70.896 (+0.891%) |

| Alexander Albon | 70.948 (+0.965%) |

| Esteban Ocon | 71.285 (+1.444%) |

| Nico Hulkenberg | 71.44 (+1.665%) |

| Daniel Ricciardo | 71.482 (+1.725%) |

| Lance Stroll | 71.563 (+1.840%) |

| Kevin Magnussen | 71.725 (+2.071%) |

| Fernando Alonso | 72.019 (+2.489%) |

| Logan Sargeant | 72.02 (+2.490%) |

| Sergio Perez | 72.06 (+2.547%) |

| Valtteri Bottas | 72.512 (+3.191%) |

| Zhou Guanyu | 73.028 (+3.925%) |

Average Race Pace:

| Driver | Pace |

| Lewis Hamilton | 78.245 (0%) |

| Max Verstappen | 78.283 (+0.048%) |

| Charles Leclerc | 78.357 (+0.143%) |

| Carlos Sainz | 78.437 (+0.245%) |

| Oscar Piastri | 78.438 (+0.247%) |

| Lando Norris | 78.443 (+0.253%) |

| George Russell | 78.5 (+0.326%) |

| Lance Stroll | 79.821 (+2.015%) |

| Yuki Tsunoda | 79.873 (+2.081%) |

| Alexander Albon | 80.056 (+2.315%) |

| Pierre Gasly | 80.138 (+2.419%) |

| Valtteri Bottas | 80.206 (+2.507%) |

| Logan Sargeant | 80.257 (+2.572%) |

| Daniel Ricciardo | 80.444 (+2.811%) |

| Fernando Alonso | 80.445 (+2.811%) |

| Zhou Guanyu | 80.786 (+3.248%) |

All Stints:

| Best Stints | Pace |

| Hamilton 3rd (26L/UH) | 75.673 |

| Verstappen 3rd (25L/UH) | 75.681 |

| Sargeant 3rd (18L/UH) | 77.127 |

| Zhou 3rd (5L/NS) | 77.636 |

| Leclerc 2nd (75L/NH) | 78.357 |

| Sainz 2nd (75L/NH) | 78.437 |

| Piastri 2nd (75L/UH) | 78.438 |

| Norris 2nd (75L/UH) | 78.443 |

| Stroll 4th (27L/NS) | 78.458 |

| Russell 2nd (75L/NM) | 78.5 |

| Verstappen 2nd (48L/NM) | 79.638 |

| Hamilton 2nd (47L/NM) | 79.668 |

| Bottas 3rd (60L/UH) | 79.84 |

| Tsunoda 2nd (74L/UH) | 79.873 |

| Albon 2nd (74L/NH) | 80.056 |

| Gasly 2nd (74L/NM) | 80.138 |

| Ricciardo 2nd (73L/UH) | 80.444 |

| Alonso 2nd (73L/UM) | 80.445 |

| Stroll 2nd (38L/UM) | 80.937 |

| Zhou 2nd (66L/NH) | 81.025 |

| Sargeant 2nd (53L/NM) | 81.32 |

| Bottas 2nd (11L/NM) | 82.206 |

Key: 1L= One Lap, 2L= Two Laps, NH= New Hards, UM= Used Mediums, NM= New Mediums, NS= New Softs

[1] I only include stints in the stint table if a driver has completed five or more representative laps, in an attempt to avoid fastest lap attempts. This has led to exclusions from the chart of everyone’s first stint and Stroll’s third stint.

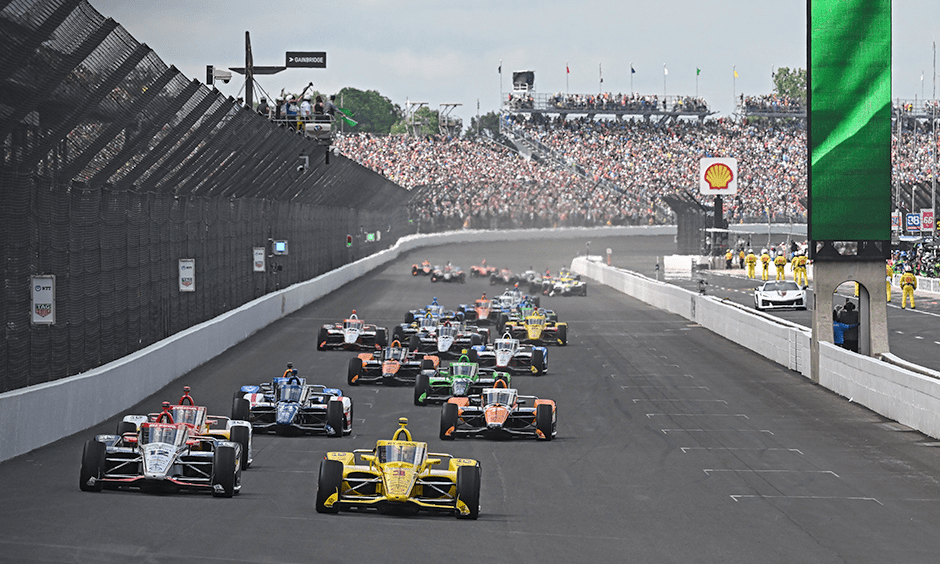

Last week’s Indy 500 was predictably fantastic. 200 laps of the greatest racing you’ll ever see, I can’t do the whole race justice. If you didn’t watch it, you were incredibly unlucky. Nothing beats the 2.5-mile oval in the heart of Indianapolis, it is exhilarating from start to finish.

A week before the race, came the two days of qualifying. Like the race itself, this is an amazing watch. Seeing laps around this speedway, it’s like watching someone drive a rollercoaster. And the narrative qualifying set in place for the race was fascinating. Team Penske delivered an amazing qualifying car, locking out all three spots on the front row, an achievement mirroring 1988. Quite fittingly, the pole sitter, Scott McLaughlin, was driving a tribute livery to the car that had won that year, the Yellow Submarine. He also set a new world record, a four-lap average of 234.22mph. The question on everyone’s mind for the next week was, would Team Penske translate their success into a race win, or would any of the challengers come good on race day?

So, race day came and……… there was a delay. A long delay. This was due to a lightning storm, definitely not the best conditions to race 200mph around an oval. So, I waited, for hours, though thankfully doing things more exciting than rewatching the Monaco Grand Prix.[1] But the race finally came, though the delay appeared to affect the drivers more than me. Because everyone was absolutely sending it, the midfield was chaos and there were more cautions than I could count. The first of these came when the rookie Tom Blomqvist put his wheels into the grass, spun and took out Marcus Erriccson in the process, to cap off a disappointing May for the former winner. These cautions bred cautions, which consequently made fuel saving less necessary than in the last few 500s, leading to the drivers racing each other even harder, breeding yet more cautions. Praise needs to go to the safety team, for how quickly they react to problems on track. They were always at the scene within ten seconds of an accident. Comparing the Indy safety team to F1’s, where it sometimes takes over half a lap for race control to call a safety car, it’s clear which sport values safety the most.

However, not all of the cautions were caused by accidents and collisions. Others were caused by Hondas. Whilst the Chevrolet engines were in danger during qualifying, come race day, it was the Hondas blowing up. Honda’s reliability woes made me worry for Colton Herta, one of the favourites to win the race. I like Colton, he’s funny, talented and attractive. If Dixon isn’t winning the race, I’d like it to be Colton. Yet, I didn’t have to worry about Colton’s engine taking him out of the race, as Colton was willing to do that on his own. Whilst Colton felt like a brand-new person this year, he made the same old mistakes, taking himself out of 2nd place and a possible win. Whilst a win would have bolstered Herta’s championship challenge, a 23rd place has done the exact opposite, to the disappointment of many an American racing fan.

Towards the middle of the race, a frantic battle erupted between Alexander Rossi, Scott McLaughlin, Alex Palou, Josef Newgarden and Santino Ferrucci for the effective lead. Every driver knew that it was vital to gain necessary track position at this point, put themselves towards the head of that train, as it would give them the best chance of battling for the win at the end of the race. Rossi and Newgarden were most successful in these struggles, but up the road, Scott Dixon and Pato O’Ward were leading, on alternative pit stop strategies. Whilst they needed to fuel save, they had a really good chance of being in the fight for the lead come the end of the race. And then came the last thirty laps.

The last thirty laps of this year’s Indy 500 was some of the greatest action I’ve seen in any motorsports race. There was a four-way battle, as Rossi, O’Ward, Dixon and Newgarden all took times leading and there were moves on nearly every lap. Initially, Dixon seemed like he might have the driver’s seat. Whilst the most successful driver currently in the series, Dixon has only won the 500 once, in 2008. As he’s the driver I support, to see him win it from his lowest starting position ever, would have been cathartic after witnessing so many near misses. Alas, his starting position did represent one truth, Dixon’s Chip Ganassi car did not have the ultimate race pace of the Penskes and the McLarens, thus he faded as the stint continued. However, a last lap move on Rossi guaranteed a place on the podium, a consultation to wrap up an otherwise difficult month of May.

As the final stint continued, the race became a two-car battle between O’Ward and Newgarden. They swapped the lead, again and again, but at the beginning of the final lap, Pato made a decisive move on the main straight. It looked like, after many heartbreaking near misses, Pato might finally achieve his dream. He put in so much work into getting to this moment and earlier in the race, had managed to save himself from two snaps of understeer, that would have, and did, put many other drivers into the wall. This was about to be his moment; Mexico was about to celebrate its first Indy 500 win. But last year’s winner had something to say about that. Josef Newgarden, the two-time champion, having waited twelve years to win his first Indy 500, made an amazing move around the outside of O’Ward on turn three, at the last possible opportunity, to win two in a row. It was heartbreaking for O’Ward, who was visibly distraught after the race, but elation for Team Penske and Newgarden, who once again celebrated in the crowd. The emotions in this race are part of what makes it the greatest, as throughout the entire month, everyone tries so hard to win. And everyone takes the emotions seriously, no failed stand-up comedy like you get from F1’s commentators, instead you get pure hype and emotion. Even viewing from home, I can feel the gravitas of this event, so I can’t imagine what it’s like in that crowd, knowing that you’re viewing the greatest spectacle in racing and then celebrating with the winner.

Thus, the Indy 500. Whilst I’ve been able to talk about my favourite moments, there’s still so much I missed. From Sting Ray Robb (yes, that is his name) leading the 3rd most laps, to Dixon’s controversial contact with Ryan Hunter Ray, to Will Power’s disappointing afternoon, going from a pre-race favourite to the wall, this race had everything. I reiterate, if you didn’t watch it, you missed out. So, remember to put May 25th in your calendar next year, avoid missing out again.

[1] I was reading a book.